Malagasy Funeral

On the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar, death is not an end to life, but an unshackling from the material world—an elevation to the powerful company of the ancestors existing as intermediaries between mortals and Andriamanitra—the sweet and fragrant Creator.

Among the Merina and Betsileo peoples of the highlands, a two-day ceremony known as Famadihana, or “Turning of the Bones,” is the greatest celebration of life and togetherness for families. Two to three years after burial, the dead are removed from their tombs, wrapped in new silk Lamba shrouds, and greeted and danced with by their families and the community. It’s a joyful occasion, not one of grief or sadness. Family members wearing woven reed hats and white shawls bring photographs and possessions of the dead.

The living reunite with their ancestors, hugging and kissing the wrapped corpses and exchanging all the news of the village for the latest happenings of the spirit world. Relatives complete the ceremony by spraying the deceased with perfume and decking them with flowers before returning them to the permanent family mausoleum. Joy at being reunited with one’s family members underscores the power of the Betsileo and Merina tradition of transforming grief over the loss of the dead into happiness and a sense of well-being.

The tombs of the Mahafaly people, built by rich families, are often made of concrete, decorated with windows or brightly painted designs depicting the lives of the deceased. Tombs are covered with images of cattle and lemurs, airplanes, taxis—even fondly remembered lovers. Throughout Madagascar the tombs of the dead are almost always more elaborate and expensive than the houses of the living. For the eighteen different cultural groups of Madagascar there is no clear division between the living and the dead—life is merely a temporary episode. At the point of death, a person abandons his mortal form to be elevated to Razana, gods on earth, or ancestors, who can affect the fortunes of the living for good or ill.

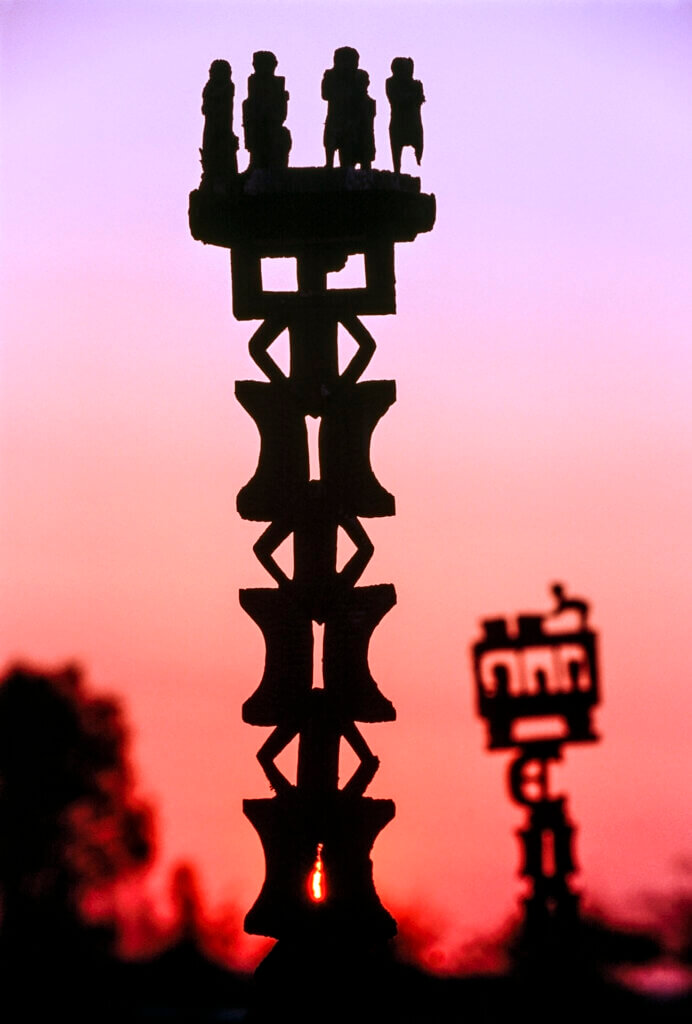

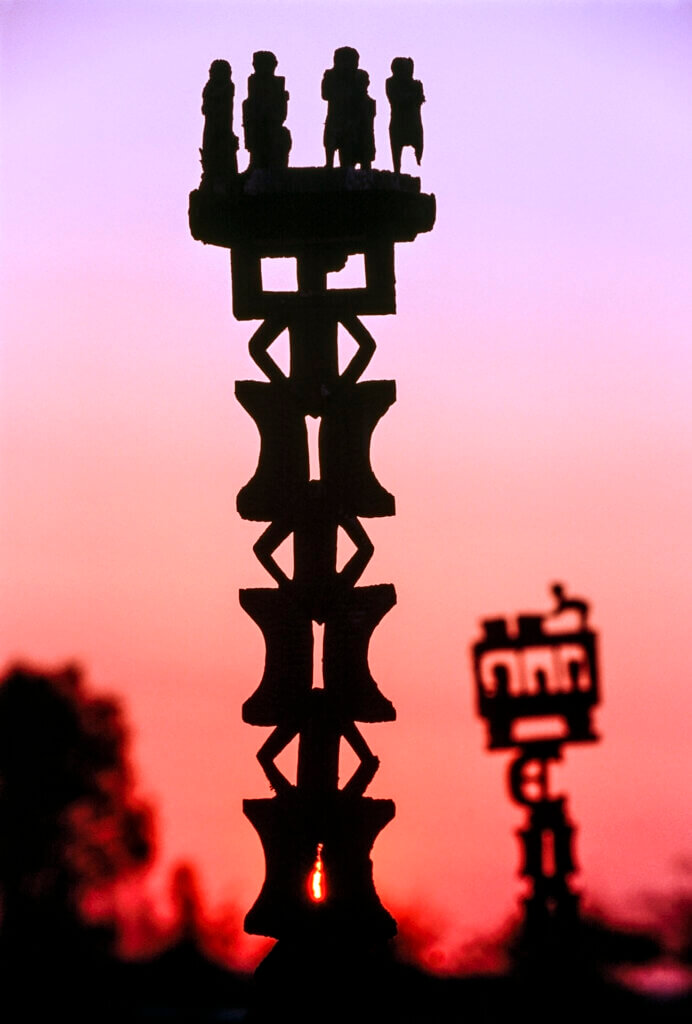

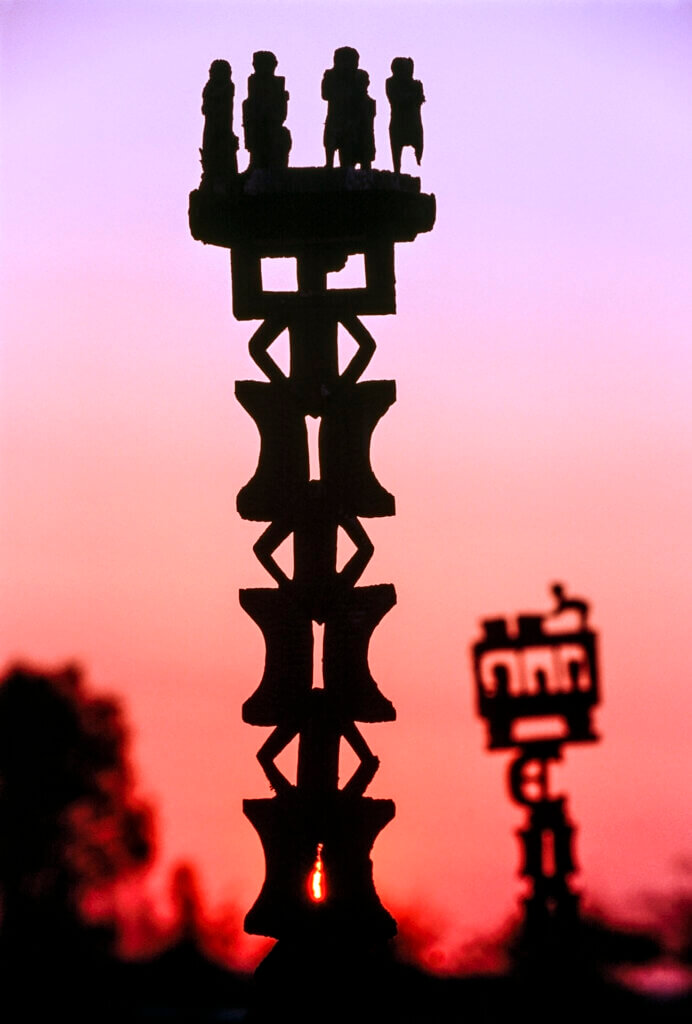

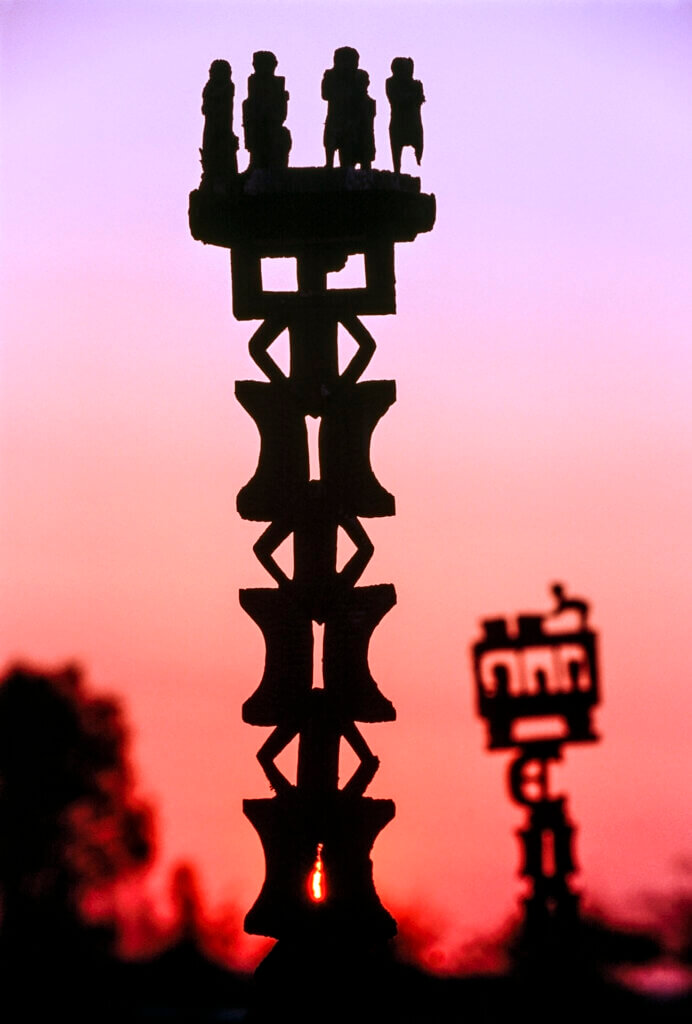

The Mahafaly royal tombs can be found in a spiny forest in the desert of southwest Madagascar. Amidst the ruins of several royal graves is the famous burial site of the 14th Century Mahafaly King Tsiapody, a vast platform of rocks sprouting hundreds of zebu horns and carved wooden grave markers like totem poles. Seven hundred cattle had been ritually slaughtered in honor of the king’s death, producing the largest and most monumental grave.

On the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar, death is not an end to life, but an unshackling from the material world—an elevation to the powerful company of the ancestors existing as intermediaries between mortals and Andriamanitra—the sweet and fragrant Creator.

More...

On the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar, death is not an end to life, but an unshackling from the material world—an elevation to the powerful company of the ancestors existing as intermediaries between mortals and Andriamanitra—the sweet and fragrant Creator.

More...