Christian Highlanders and Falasha Jews

Lalibela, the 12th Century capital of Ethiopia appears to be a simple mountain village, but underground it hides a magical world of thirteen monolithic churches, hewn from the red volcanic rock on which they stand.

Known as the eighth wonder of the world, the Lalibela churches are veritable fortresses, each one being connected by narrow underground passageways to hide and protect the Christian community during the times of Islamic invasion.

To this day the construction of the churches still remains a mystery. According to legend, the church of Saint George, Beta Giyorgis, took forty years to carve and this was personally supervised by the patron saint himself, assisted day and night by angels. To this day one can see the hoof prints of Saint George’s horse, embedded in the church’s southern courtyard.

In the Ethiopian Christian calendar year there are over two hundred religious holidays, including saints’ days. Among the most important are Christmas (Genna) on the seventh January and Epiphany (Timkat) twelve days later. At this time tens of thousands of pilgrims gather, having walked for days and even months to participate in these ceremonies, such is their conviction to the Christian faith.

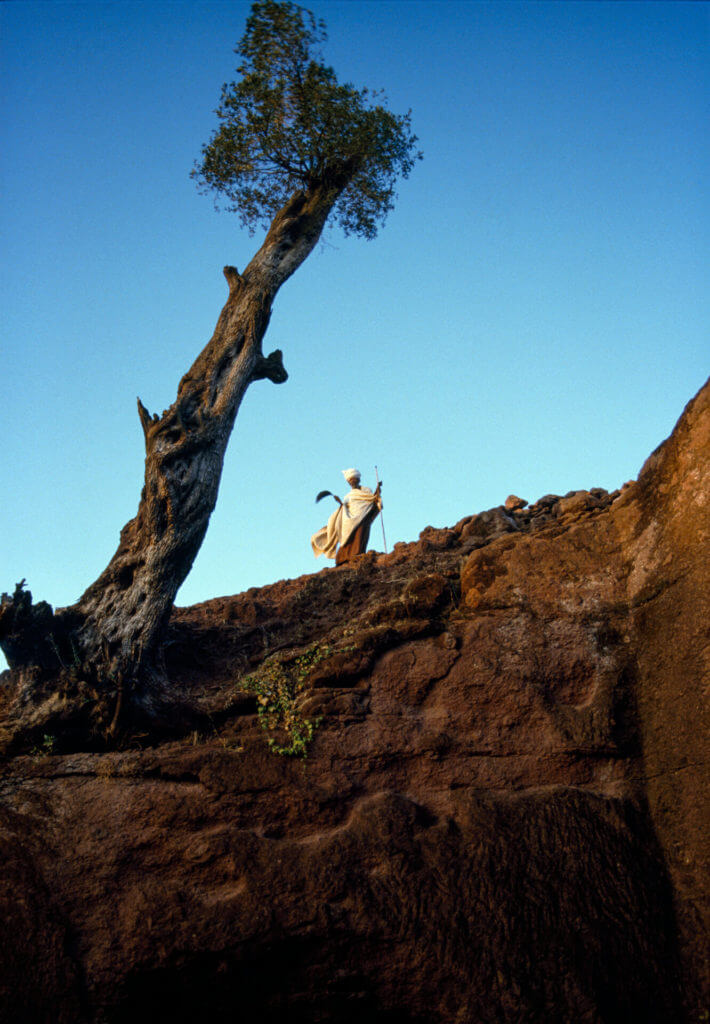

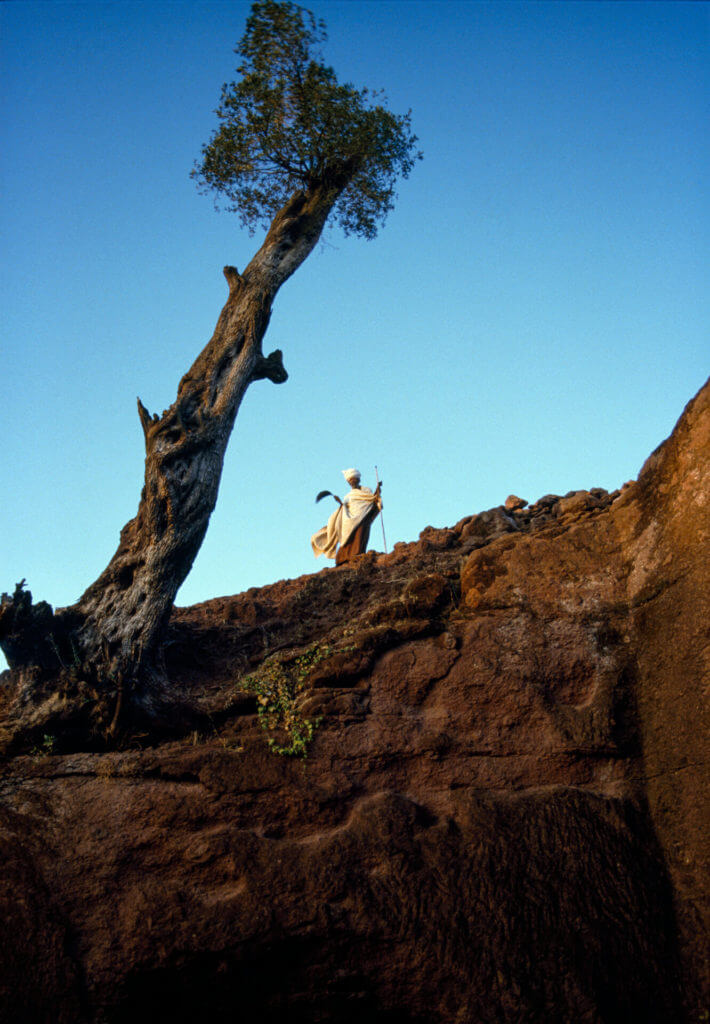

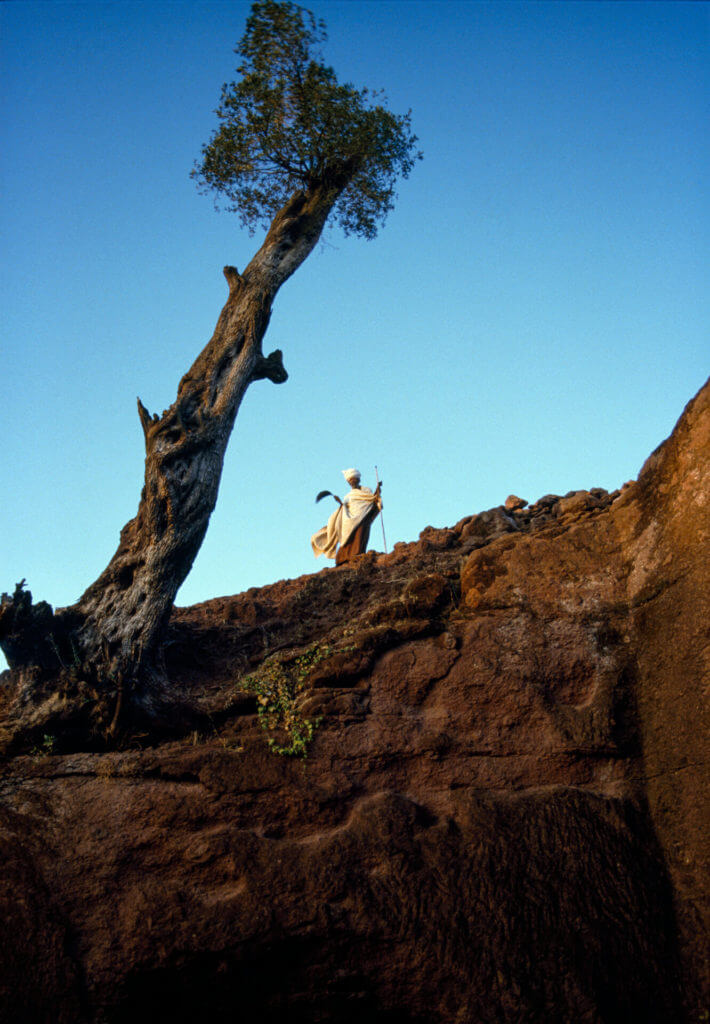

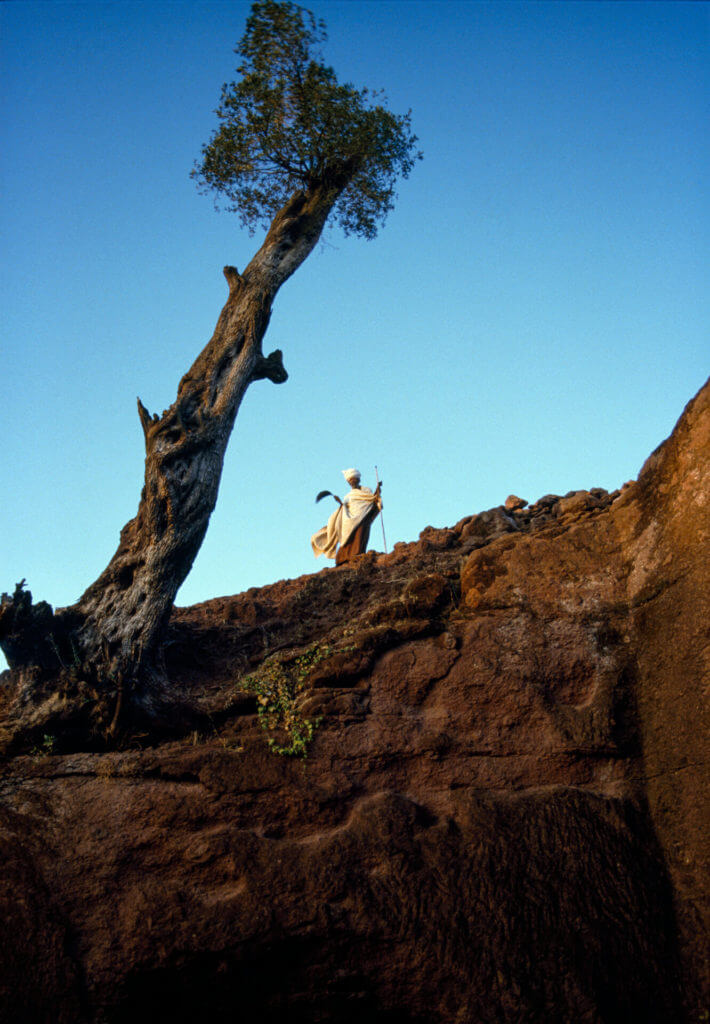

At Christmas, following an all-night vigil in the church of Beta Maryam, the pilgrims gather in the courtyard and begin circling the church, following priests carrying richly embroidered velvet umbrellas and swinging censers filled with frankincense and myrrh. The priests then mount the walls overlooking the church, and chant prayers to the congregation below who chant back in a call and response fashion, symbolising the union of heaven and earth.

At Epiphany, twelve days later, the holy Tabots—slabs of stone, wood, or gold, incised with the Ten Commandments— are brought out of each church. Wrapped in richly embroidered silks and brocades so they cannot be seen by the eyes of laymen, the Tabots are carried on the heads of turbaned priests in a glorious procession to two tents, symbolic of the tabernacle beside Lalibela’s River Jordan. Preceding them are younger deacons wearing filigree crowns and carrying ornate crosses, and others holding aloft multi-coloured umbrellas representative of the celestial spheres.

At sunrise the following morning the baptismal ceremonies of Epiphany begin. The priests dip their processional crosses into the baptismal water of the River Jordan and pilgrims splash each other with holy water, symbolising the baptism of Christ by John the Baptist. Following this, in a dramatic procession, the Tabots are returned to their respective churches and placed in the holy of holies, a sanctuary deep within the church concealed behind curtains and hidden from the eyes of laymen until Timkat the following year.

Gondar, the 17th Century Christian capital of Ethiopia, and Lake Tana, to the south, are renowned for their tradition of Christian painting. There are 37 islands in Lake Tana, each with monasteries filled with paintings.

Emperor Fasilides, who founded Gondar in 1635 was greatly interested in architecture and was responsible for seven churches. His grandson’s greatest achievement was the building of Debre Berhane Selassie church, decorated with a great variety of scenes from religious history. It is renowned for its ceiling of more than 80 archangels whose eyes are believed to follow each and every movement of the pilgrims that come to pray. Hundreds of equestrian saints with their spears are depicted on the walls of the church, busy chasing non-believers out of the Christian capital. Their lifelike qualities, combined with a Baroque richness of design and warmth of color distinguish the paintings in churches and monasteries in Gondar and Lake Tana.

In the region of Gondar, the Falasha Jews, who call themselves Beta Israel, meaning the House of Israel, lived as neighbours to the Christian Highlanders. On the surface they shared a similar lifestyle, they have similar dress, similar architecture and they both lived by cultivating the land.

Unlike the Amhara, Falasha men frequently worked as blacksmiths, weavers and tanners while the women make finely crafted pots and baskets. The most important difference between the Falasha and the Amhara is religion, the Falasha adhere strictly to the teachings of the Torah, particularly to the Five Books of Moses.

Isolated from other Jewish communities for over two thousand years, the Torah used by the Falasha is written not in Hebrew but in Ge’ez (the ancient liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthadox Church) and many Falasha have never spoken Hebrew. Our visit occurred just before Operation Moses when thousands of Falasha Jews were airlifted from Ethiopia to Israel “The Promised Land” during the famine years of 1984 -1985.

Lalibela, the 12th Century capital of Ethiopia appears to be a simple mountain village, but underground it hides a magical world of thirteen monolithic churches, hewn from the red volcanic rock on which they stand.

More...

Lalibela, the 12th Century capital of Ethiopia appears to be a simple mountain village, but underground it hides a magical world of thirteen monolithic churches, hewn from the red volcanic rock on which they stand.

More...